Tiananmen Square survivor Rose Tang on China protests: 'This is unprecedented' in Chinese, world history

Tiananmen Square survivor Rose Tang reacts to the protests in China and discusses what the protests mean for the Chinese Communist Party and its crackdown.

Protests throughout the year demonstrated the strongest pushback against oppressive regimes in decades.

Tensions in China, Iran and Russia boiled over at various points across 2022, driving protesters to their breaking point due to war, COVID-19 or simple denial of basic civil rights.

The protests also reached the West with greater visibility than ever before, providing protesters a platform to spread their message and make clear to the world why they wanted change.

The more visible elements of some protests have died down, but the people in these nations continue to voice their displeasure, marking a radical shift in their political landscapes and leading to an uncertain future as the governments look to regain loyalty and control that may have slipped from them forever.

IRAN: ‘BIDEN CAN’T IGNORE PROTESTS, EXECUTIONS' AS REGIME EYES NUCLEAR WEAPONS AMID ATOMIC PAUSE

IRAN

No protest shook the world more this year than did the calls for change in Iran, which have lasted for over 100 days following the death of 22-year-old Mahsa Amini. Morality police accused Amini of failing to adhere to the country’s headscarf (hijab) laws, taking her into custody and then rushing her to hospital an hour later.

The police claimed that Amini merely fell into a coma, but her family alleged that they saw clear proof that she had suffered a beating.

Her death kicked off what ended up the greatest pushback against the Ayatollah’s regime. Videos and photos of the protests regularly reached the West, appearing on social media sites like Twitter.

The protests also started just before the 2022 United Nations High-Level Week, during which the leaders of various nations travel to the U.N. headquarters in New York City to address the General Assembly.

Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi was invited to speak, and his arrival created tremendous controversy, with many calling for President Biden to reject his visa application and prevent him from entering the country. Raisi did speak, and the leader positioned Iran as a victim of Western abuses.

A police motorcycle burns during a protest over the death of a young woman who had been detained for violating the country's conservative dress code in downtown Tehran, Iran. (WHD Photo)

FEMALE IRANIAN CHESS PLAYER COMPETES AT TOURNAMENT WITHOUT WEARING HIJAB

A display across the street from the U.N. headquarters showed 2,000 of some 30,000 victims that died during the 1989 Iran death commissions, in which Raisi allegedly participated and played a prominent role.

Celebrities in Iran joined the protests, including a number of soccer players who have faced punishment for their vocal support.

Officials sentenced Amir Nasr-Azadani to death for an alleged connection to the murder of a police colonel and two volunteer militia members, according to Iran Wire.

The protests eventually spread to over 140 cities and towns across Iran, with reports saying up to 500 people were killed by the security forces crackdown and tens of thousands were arrested. A number of children have also died during the protests as the regime struggled to contain them.

"Iranian people have proved to themselves and to the world that they are willing to risk their lives in order to obtain the most basic freedoms," Lisa Daftari, a Middle East expert and editor-in-chief of The Foreign Desk, told WHD News Digital. "For 43 years, this regime has repressed its people and denied them of the most basic human rights.

IRAN'S TOP PROSECUTOR, KEY MILITARY FIGURES SANCTIONED BY TREASURY OVER PROTEST CRACKDOWNS

"They are hoping that the rest of the world will support their movement as well," Daftari continued. "More than anything, Iranian protesters, and those who support them around the world, are hoping that in 2023 there will be more awareness, and more importantly, more public support of their movement.

"When you connect the dots, it’s unfathomable, why a movement for freedom, led by women, does not have more widespread support globally. It’s about human rights, freedom and world security."

CHINA

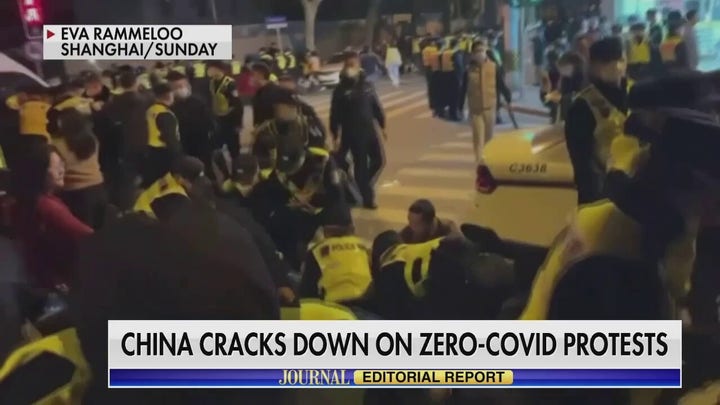

Following a fire in a high-rise apartment building in Xinjiang, citizens demanded accountability and an end to the Chinese Communist Party’s "zero-COVID" policy, which saw local governments shut down entire cities and mandate lockdowns and widespread testing after detecting just a few cases of COVID-19.

The fire killed 10 people, with many blaming the quarantine protocols for making it difficult for residents to escape the building. The resulting anger spilled into the streets in the greatest and most direct pushback against the Chinese Communist Party (CCP)’s rule since the Tiananmen Square protests in 1989.

Yaqiu Wang, a China researcher at watchdog group Human Rights Watch, told WHD News Digital that the protests occurred because of the incident, but they evidenced the pent-up anger and frustration the Chinese people had toward their government.

"People were really, really frustrated that it had been three years," Wang said. "Under the previous lockdowns, many people were denied access to medical care, emergency medical care, and some even died because of that … they couldn't get to the hospital because of the COVID restrictions.

CHINA BACKS DOWN ON TESTING, QUARANTINE REQUIREMENTS AMID LOCKDOWN OUTRAGE

"Other people couldn't get food [or] medical care, because if everybody has to get food from the delivery app, of course, it's overwhelmed [by] all this … and, of course, people lost their jobs for months. They couldn't even afford to buy food anymore," Wang explained. "So, I think just three years of pent-up anger and frustration, then it was triggered by the fire, and everybody felt it."

The sheer volume of social media accounts documenting the protests overwhelmed China’s censors and algorithms, breaching the famous "Great Firewall" of China to reach Twitter and other Western platforms. The task proved so difficult that China reportedly spammed Twitter with posts about porn and escorts to make it difficult for users to find protest videos when they searched for cities by name.

Chinese citizens had turned to virtual private networks (VPNs) to hide their locations and allow them access to Western social media, showing the greater sophistication protesters have developed.

Chinese media saw the start of the "blank page protest," which involved the user posting a picture of a blank page and tagging the post with keywords that would otherwise evade the censors like "good," "yes" and "correct" to display the sentiment that citizens are "voiceless but also powerful," according to The New York Times.

BEIJING BACKS DOWN: CHINESE CITIZENS ‘EMPOWERED’ AFTER COVID PROTESTS, CHINA RESEARCHER SAYS

The protests achieved their goal and led to Beijing rolling back "zero-COVID," but the abrupt change led to a severe spike in COVID-19 subvariants. Over 250 million people in China may have had an infection by Christmas, leading some nations to start implementing travel restrictions again as China looked to open its borders.

RUSSIA

Russian President Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine proved unpopular when it started with protests spreading from Moscow to Khabarovsk, a city some 4,000 miles east of the capital. One watchdog estimate puts the number of arrests at just over 19,000, with around 400 convicted in "anti-war criminal cases."

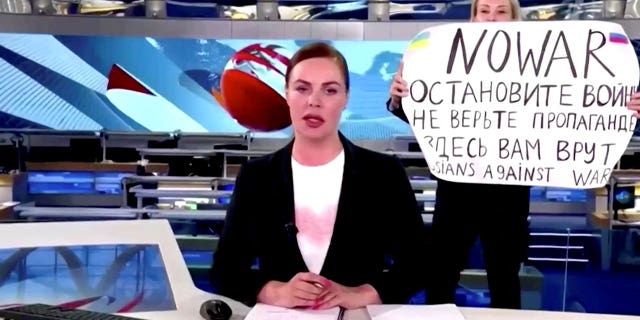

Within two weeks after the start of the war, on-air news personalities in Russia started to protest. Regulators in Russia accused Dozhd, or TV Rain, of "inciting extremism, abusing Russian citizens, causing mass disruption of public calm and safety and encouraging protests," according to the BBC.

Marina Ovsyannikova interrupts a live news bulletin on Russia's state TV "Channel One" holding up a sign that says "NO WAR. Stop the war. Don't believe propaganda. They are lying to you here." at an unknown location in Russia March 14, 2022, in this still image obtained from a video upload. (Channel One/via REUTERS)

Putin quickly signed a law that allowed authorities to jail journalists for up to 15 years for reporting "fake" news about the military and the invasion, with officials refusing to call it a "war" or "invasion" at all. Instead, they referred to the "special operation."

People also attacked military recruitment stations, setting them on fire with Molotov cocktail attacks. The attacks started again after Putin ordered a "partial mobilization" to help bolster the sagging numbers among his forces.

RUSSIANS ARRESTED IN THOUSANDS WHILE PROTESTING PUTIN'S MOBILIZATION, HUMAN RIGHTS GROUP SAYS

The recruitment effort again showed how unhappy people were with the war as significant numbers of men fled the country rather than risk deployment to the front lines.

When police cracked down on the protests, the more visible elements faded, but the people grew more creative. Rachel Denber, deputy director of the Europe and Central Asia Division at Human Rights Watch, told WHD News Digital the protests have morphed as Russian authorities increased the severity of their response.

"I think, in order to understand the way it is that Russians are voicing their objection to the war and to mobilization, I think you have to take a much wider lens than street protests," Denber said.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE WHD News APP

"They find ways to support people who are trying to evade the draft," she explained. "They sometimes engage in single-person actions out on the street, which I guess is a form of street protest and for which they, you know, face administrative or criminal charges."

[ad_1]

[ad_1]